I've already posted two installments of the not-in-Scotland October

weekend without describing the trip's core mission: attending the "Community Open House"

of the National Yiddish Book Center, following a postcard invitation and the cancellation

of our Scotland plans. Aplologies. Over six or seven weeks, this task has languished,

stopping up the flow of at least four potential posts.

|

| The main room of extra copies of rescued Yiddish books at the Center -- waiting for homes |

I love this place for bringing all this Yiddish back to me from

long-term storage. The old books on the

rows of shelves, extra copies waiting to be bought and read, are a perfect

physical analog to the dormant vocabulary in my head waking up and getting

exercised. And all brought back from a time I looked like the young romantics here,

except perhaps for the purple hair.

|

| Can you make out the "shrekliche" disaster reported on here? No peeking on the bottom! |

While I've earned my special affinity by virtue of

courses taken decades ago, the Center

also tries very hard to draw in those who don't speak the language a bit. There are exhibits tucked in among the books;

an exhibit of great Jewish moments in popular films and TV shows; front pages

of the Yiddish press on historical news days, with translated headlines; old

Yiddish linotype machines and their histories; stories behind the translations

of great works; pictures and old home movies of an ethnomusicologist's travels

through Eastern Europe. There's also the huge original crate, pried

opened with (replaced) books spilling out in a prominent place on the floor, which

was sent from the evaporating Jewish community of Zimbabwe.

|

| Who knew? |

|

| Exhibits educate the Yiddish deprived. |

Once inside, a Yiddish, entre-nous (tsvishn unz) sense of humor permeates the place along with its eagerness to teach; one of the rest rooms is labeled Vu Der Kaiser Gait Alayn.*

|

| Yiddishist-in-training giving a tour beside the crate of books from Zimbabwe. |

I love this place for memorializing its poets and playwrights on slate squares, in Yiddish and English, over engravings of leaves, among the outside plantings.

|

| The Writer's Garden |

|

| English-to-Yiddish is in the works |

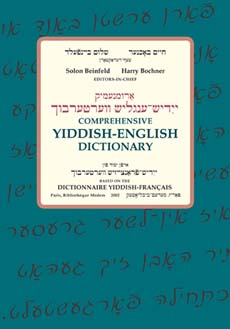

Beyond the main room of books, there's an auditorium where Dr. Harry Bochner and Professor Solon Beinfeld, sixty- or seventy-something editors of the new Comprehensive Yiddish-to-English Dictionary, are being interviewed on stage by young Josh Lambert, academic director of the Yiddish Book Center and visiting English Professor at nearby U Mass. The dictionary, the first since Uriel Weinreich compiled his back in 1968, has just been published. These philologists are describing how it differs from its predecessor. For starters, it has 50 percent more words. The editors got a great leg up on their project through the efforts of a new Yiddish-French dictionary, whose authors Yitskhok Niborski and Bernard Vaisbrot created the large corpus of Yiddish words. They say it's also easier to use, without all the cryptic abbreviations.

This volume also includes words Weinreich simply didn't

like; his dictionary is famous, for example, for leaving out the dirty words

and even "tuchis," one of

the best-remembered Yiddish words that ever lived. It also includes words with the German-type

spellings that were favored by socialists.

Adamant secularists, they didn't want speakers to have to refer back to

their religious educations to know the original vowel-free spellings of Hebrew words, which keep their original forms when passing into Yiddish.

|

| Linotype machine |

The Forward newspaper put up some of the funding for the verterbuch, with the understanding that this lexicon would be used to help readers understand their Yiddish online edition. Some also came from the University of Indiana, whose press is the official publisher.

The day proceeds with campus tours, including descent into

the climate-controlled archive in the basement.

Oddly, they tell us that everything to be digitized is schlepped to

Israel for this process and then schlepped back. And Hebrew-character OCR and indexing,

performed pro bono by Assaf Urieli, a computational linguist in the French

Pyrenees, will ultimately render the Center's whole collection of books searchable online.

The day ends with a Q and A with Aaron Lansky in the bigger

auditorium, followed by a great performance by klezmer duo Debbie Strauss on

violin and accordion and Jeff Warschauer on guitar and mandolin. They don't do the Yiddish standards, but gems I've never heard before.

|

| Aaron Lansky |

On the way out I buy, for eight dollars apiece, part II of Sholem Aleichem's wonderful Motel, Peysi the Cantor's Son in the original, a Workmen's Circle Yiddish children's textbook from the sixties, and a book of poems in Yiddish and Hebrew. I also buy a copy of the dictionary, just to show

support. Did they know my Rutgers teacher,

writer Wolf Younin?, I ask, while they sign the book. Dr. Bochner says he had

heard of him. Later that evening, in

downtown Amherst, we bump into him with friends at Moti's, the local middle eastern

restaurant. We try to cozy up, even peripherally, with the few families who constitute the Yiddish pillars of Boston.

* "Where the Kaiser goes alone."