The three of us, led by Jakub, went into Przeworsk's

Ratusz/town hall to look for records, as municipalities are supposed to hold those

that are less than one hundred years old.

Older than that, and they go into regional Polish archives in bigger cities; in

Przeworsk's case, Przemysl.

The entrance to the Ratusz was now in the back, in

a new addition whose construction was photographed the day Google came by in

2013.

Now it was finished and little kids played by the fountain.

We came to an office occupied by two women in their sixties;

John Paul II's picture was on the wall.

Jakub explained the reason for our visit and they explained back,

through him, that they couldn't help us; only marriage records were kept

there. We wanted another municipal

office, they said; the one by the elephants.

Elephants? Were they

pulling our leg? We walked to Jakub's

car, looking for elephants on signs or in store windows, then went a few blocks

west on E40 until we came upon a pair of elephants on the road's grassy median.

They were topiaries. Cute green elephants,

made of hedges, with red carpet saddles. And across the street from them was

another office building, at the end of a flowery walkway, showing Przework's by now familiar coat of arms, with

the star and crescent.

Actually, I think there's something between Poles and

elephants. They're a motif I saw painted on baroque buildings in Tarnow and elsewhere.

Anyway, we entered this municipal building, whose halls

looked just like town halls anywhere, with signs boosting Przeworsk and everything that happens there,

culturally, athletically, educationally, commercially. We were directed up the stairs to another,

smaller office, where two younger women, sitting at keyboards, also listened to

our quest via Jakub.

They were very sorry, but Przeworsk was no longer holding

any town records; everything, recent to ancient, was now stored in Przemysl.

Disappointing, but Przemysl was on our itinerary that day, anyway. I saw a map of Przeworsk on the wall, the

kind framed with squares of local advertising, and asked them if they had any

more copies. They apologized again. We thanked them and went back down the

stairs.

Before we reached the first floor, the women called down

after us and gave us the map from the wall, rolled up; a consolation prize. I now have a nice map of Przeworsk and

immediate vicinity, with the ads of many local businesses, mostly in home

improvement, all around it.

Suzanne

Wertheim's web page on Przeworsk had mentioned a local teacher, a Mr.

Thomas, who had helped her identify old sites from pictures. Jakub thought of inquiring in Przeworsk's

public library -- also conveniently

located near the elephants. I sat down at

a PC and launched the familiar refrain of a Windows boot-up while he went

to ask the local librarians if they knew

of this teacher. Again, no luck. And not much English, not even from the young

civil servants. Sympathetic smiles, at

least. And Windows, in Polish.

We were about to set out for Przemysl, the town after

Jaroslaw, when I remembered that I'd seen a Przeworsk museum on the web. That too, was nearby, in a park that had been

another Lubomirski estate. The museum itself looked like an old elegant

country house.

I wasn't sure why I thought of the museum; I wasn't much interested in the case of surviving Judaica mentioned on their site; I know what menorahs and tefillin look like. Nor did we want to see any more aristocratic interiors, or the historical firefighting exhibit. Again, another entrance, another explanation in the native language.

I wasn't sure why I thought of the museum; I wasn't much interested in the case of surviving Judaica mentioned on their site; I know what menorahs and tefillin look like. Nor did we want to see any more aristocratic interiors, or the historical firefighting exhibit. Again, another entrance, another explanation in the native language.

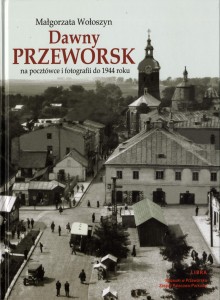

But this time we stirred up some enthusiasm. Wait, let us get the local historian, they said. Turns out she worked upstairs. Here, look at these books, in this case. Here's a book of photos on the history of Przeworsk with a lot on the Jewish community, edited by this same historian.

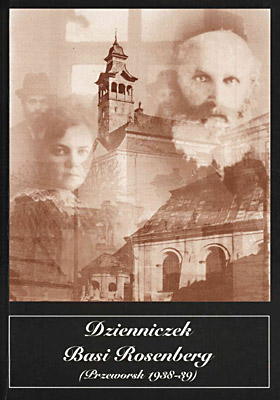

Here's another book; a diary, by the Anne

Frank of Przeworsk, one Basia Rosenberg.

Well of course I bought that, and for only 8 zlotys. Yes, it's in Polish. I'm working on it.

Here's another book; a diary, by the Anne

Frank of Przeworsk, one Basia Rosenberg.

Well of course I bought that, and for only 8 zlotys. Yes, it's in Polish. I'm working on it.

I would have been delighted to buy the book of photos, too,

if that hadn't been their last copy. One of only 1000 or so printed, it was out of print. I'll be looking for it on Polish ebay. We were ushered up the stairs to meet the

historian, a woman somewhere near 40, I think, by the name of Malgorzata (Margaret) Woloszyn. She and a colleague

were working on computers in a cramped paneled

room, and when we greeted her and explained our mission, she went into a back

room and came back barely minutes later with some 95--to-100-year-old books of

handwritten census records.

One book was an index to the others. And there, in those old lined but still sturdy pages, Margaret turned the pages to Schopfs and Schillers. Including my

grandmother, and her sisters, and brothers, and many cousins I never knew

about, their birth dates, names and relation to their households, and the

occupations of the head of the household, which was Krawic, or kravitz. This

means tailor, which matched what I already knew.

We were all very happy, finder, researcher,

interpreter/guide and husband. Here was proof, still in Przeworsk, that my

grandmother, and therefore I and my family, had some connection to this

town.

I asked her if she

got visits like this much, from roots seekers, and she said that yes, she gets

a few every year.

I was so excited that I took a lot of blurry pictures of the

pages, and accidentally used the flash twice in spite of promising not to. Some are sharp. At least one page I'd like to ask her to

reshoot and send me.

And I can, because I asked for her email address and she

gave it to me. I gave her my card and

she stapled it into some kind of guest register. And as

soon as I finish this series -- or maybe even this post -- I'm going to write

her, and Google Translate will do the rest.

The fact is that millions of birth, death, military and

marriage records of Polish Jews are now searchable on the web. I've found many and expect to find more. The

Mormons gave Poland lots of money and resources to digitize all these records,

in their dubious but indirectly useful effort to posthumously baptize everyone

who ever lived. So it doesn't really pay

to spend too much of a short in-person visit in dusty archives. Ms. Woloszyn herself said that these census

books were going to be digitized as well. But there's still a satisfaction in

seeing and smelling pages in ink and paper, in a tangible ledger, in seeing the

names in that elegant turn-of-the-century penmanship. In being in the same general

place where they were written, so long ago.

Now here's a really strange thing: The historian's last

name, Woloszyn, is the last name of some of my husband's cousins. Bruce Wolosin,

his third cousin originally from Cleveland, today lives in the same town we do and

he and his wife are active members of my synagogue. Volozhin is a town once

famous for its rabbinic learning.

I'm sure this helpful historian isn't Jewish. Jesus' picture hangs on her office

wall, too. But maybe, if you do some

research...

You've done an amazing amount of research! And yes, the script in the ledgers is gorgeous. Have you made connections with any long lost cousins?

ReplyDelete